Any boat on the water using a diesel motor can be stopped dead if microbes turn your fuel into a black stringy sticky mess that gums up filters and feeder tubes. It happened to me and I fixed it by cleaning the fuel system (including both tanks) and installing a magnetic fuel filter.

The three essentials for a smooth operating diesel engine are clean air, oil and fuel. The last item can let you down even if all the filters are brand new. An engine failure caused by unknown contaminants in my fuel tank prompted me to fit a magnetic fuel treatment system.

In the process, some research led to some interesting findings.

The engine had stopped just outside Wellington Harbour in rough seas while crossing Cook Strait to the North Island of New Zealand. While motor sailing against a stiff wind into a bay, diesel tank sediments had shifted and blocked the outlet at the base, causing air to be sucked down the breather pipe into the engine which of course spluttered to a halt. After switching tanks, the irksome task of bleeding fresh fuel to the engine in rough seas was a reminder that you don’t mess with Cook Strait.

At anchor, some detective work. The tank outlet valve was blocked, but a hooked wire poked through the outlet pulled out a black, stringy viscous substance that looked like something out of a gunge horror movie. A litre or so of diesel that was tapped off was badly contaminated along with about a small amount of dirty water, and the remainder was a pale and cloudy.

I guessed that the black stuff was Hydrocarbon Utilising Microbes (HUM bug). A shock dose of biocide would knock any remaining blighters off their perch, until I could empty and thoroughly clean the tank interiors. For seven years, I had been using a ‘home remedy’ of naphthalene – the principle ingredient of moth balls – but something stiffer than this was needed to rein in the new problem if we were to complete our voyage to the north coast of the North Island. Grotomar 71 was the biocide of choice. It had been consumer tested by a UK boating magazine as one of the two best on the market.

Microbes or fuel precipitates?

The gunge that came out of the drain was either dead microbes from previous treatments, or a precipitate of fuel fractions. I was stabbing in the dark here, since it was difficult to tell unless professionally examined. However, sifting through Dr. Google’s pages, and some amount of chin wagging with engineers brought up some facts and opinions.

On our cutter Wild Bird, after 20 years of diesel fills, certain distillate products, such as light ashpheltenes (a mixture of paraffin waxes and resinous gums) probably precipitated onto the tank interior. We had sailed between the climatic extremes like Nova Scotia and the tropics. Wax compounds in diesel for cold weather operation probably came out of solution in the warmer climate.

Sediment can also be present in diesel, if you are sourcing from less than optimum outlets. In Indonesia, where I was motoring for days on end to break through the sultry doldrums at the equator, diesel had been sourced from a fisherman’s private supple in a 44 gallon drum.

A little history. The first diesel engine built was designed to run on pure peanut oil, a simple hydrocarbon liquid. Today large diesels use heated bunker oil, and small diesel engines normally are fed a complex mix of refined fractions. Since fuel fractions that make up diesel differ between countries, it is not surprising that when mixed, some components might precipitate out of solution. Thus the story of diesel in your tank is not as simple as it appears. A cocktail of physical and chemical factors conspire to subvert our idea of a perfect fuel, so the upshot is that no matter what occurs, gunge might still form in your tank and the only way it can be removed is by physical cleaning.

Inspection hatch.

Just a small problem existed. The tanks had no inspection hatch. Human eyes had never seen the interior in 20 years so. The tanks were 4mm mild steel welded integrally to the hull, with a longitudinal baffle. Once inside, I found the interior was indeed coated with a black gooey muck that wiped off easily. I mixed a sample of this with water and left it in a warm place for a week to test for microbe growth. A week later, no HUM bug had grown but this was probably because of residual biocide.

After cleaning the tank interior, I sprayed biocide on the interior surface, prior to fitting the lid and filling with fresh diesel. Long term I wanted a chemical-free treatment to keep the diesel pristine if that was possible.

De-Bug magnetic fuel treatment system. When Jon Drumm of Advanced Diesel Solutions heard about my plight he recommended their smallest De-Bug unit L140 (for fuel flow up to 140 litres per hour, or for 75 kw/100HP). The fuel circulates around fixed magnets so that the microbes experience a magnetic field which rapidly oscillates between north and south. The De-Bug causes the microbes to burst then break up into particles small enough to pass through filters prior to being burnt in the engine. Drumm was keen to note the differences between De-Bug and other designs. He says that De-Bug tri-stack design incorporating three magnets is superior to a system which has only one or two magnets. During research, they discovered that the oscillating field a microbe experiences in a ‘tri-mag’ stack is much more deadly than the magnetic field in other simpler systems, which might have needed extra anti-microbe measures such as UV treatment. The tri-mag design imposes a strong oscillating N/S and S/N polarity change that is much more destructive to HUM-bugs.

HUM bugs in diesel can vary in size from 3 to 10 microns. These are normally bacteria or fungi. Therefore if the primary filters are between 10 and 30 microns, then the fuel should polish up or purify well with each pass through the De-Bug unit, filters and then back to the tank via the overflow. Although in my case, since only about three litres per hour is being burnt, the remaining returned fuel (see below) contains destroyed microbes that either become part of the tank sludge for removal later, or are burnt in the next pass.

Of course, in commercial vessels, fuel doesn’t get much chance to settle. Most dead microbe matter will remain in suspension until it is burnt in the engine.

In my case, the test will be long term, the results measured by clarity of fuel and lack of problems. Shortly after using the De-Bug system, the fuel in the sight tube changed from a cloudy light brown to a pale clear solution, and now after four months remains clear.

Fitting the De-Bug filter.

Installation was a breeze. The De-Bug unit is simply included in the fuel line in an upright position, before the primary filters, which allows the broken down microbes to pass through to the engine for destruction. 97.6% of microbial matter is destroyed on each pass through the De-Bug, and the unit should last 20 to 50 years. To work properly, the flow rate (used fuel plus fuel that is returned to the tank) should be sufficient to allow good ‘polishing’ of the fuel.

I had measured the return rate for my 38kw/50HP Nissan SD 22 at 20 litres/hour. This was done by taking the return line and measuring a small amount and timing it so I could then extrapolate using simple maths. Jon Drumm confirmed that 20 litres per hour would be sufficient for efficient operation. Over time, fewer bugs should be present. However remembering the tango rule, microbes can under optimum conditions (warm and on a water interface) go to town. They can divide once every 20 minutes. One randy HUM bug can wreck your summer.

[Sidebar:] Survey of users.

Mike Chaplin of Seapower, in the Opua Industrial Estate services commercial craft operating in the Bay of Islands. He has installed large De Bug units on boats operating there. He also mentions the need to have sufficient flow rate through the filter for it to be effective, otherwise the polishing effect on the diesel does not take place. Obviously, the tanks have to be clean to begin with, and the best results are in boats with a constant use of fuel so that fuel is not lying in the tank for considerable lengths of time. Mike says that diesel conditioner and biocide is usually used in conjunction with the De-Bug unit.

Mike has had good reports from frequently used boats where the unit is installed. Seapower usually installs a full ‘sterilization’ process utilizing UV, water traps, De-Bug, and both primary and secondary filters. On the other hand, in private craft, a good inspection hatch is important so that accumulated ashpheltenes and dead organic matter can be cleaned out.

Other private users surveyed who use De-Bug report good results. No one with an installed De-Bug system has had microbe problems, although one person who had an early generation De-Bug had white deposits on his filters. (The early generation De-Bugs had only two magnetic rings, but that was improved when three were incorporated into the design.)

Occasionally I came across people who used neither De-Bug nor fuel conditioner. One launch boat owner in Westpark Marina uses a small secondary diesel tank that is fitted with a hospital grade UV light that kills microbes prior to filtering.

Several years ago I was delivering a sail boat to Brisbane from Samoa when the De-Bug unit became clogged with a black gunge after some rough water motor sailing. However, the 20 year old tank had no inspection hatch and without an analysis, we could not tell if the gunge was microbial in nature. It could well have been normal fuel fractions precipitating out which were then picked up by the outlet.

Conclusions:

Good housekeeping should ensure minimal problems. Clean tanks, clean fuel, removal of bottom water, (since it drops below diesel) appropriate primary and secondary filters, a De-Bug unit and regular use of the engine should keep you going. Otherwise, add biocide and fuel conditioner if your engine is not used on a regular basis.

[Sidebar:] Analysing diesel fuel for contaminants.

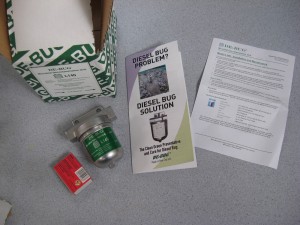

If you are unsure of your fuel condition, Gough’s fuel analysis lab has a sample kit that is posted to you. They claim that with optimum conditions, a single microbe can multiply to a mass of 10 kilograms in 12 hours resulting in a mat on a fuel/water interface of several centimetres thick. Jovar Bonagua from the lab informed me that the kits can be purchased then sent back with your fuel sample for testing in their lab. Fuel should be taken out of the tank bottom drain. The kit contains bottles, label, shipping bucket with yellow lid, and a courier label all designed around the problem of shipping a hazardous substance UN3082. The samples must only be shipped to Goughs in the special containers to prevent any possible environmental spills.

Your results are given by accessing their website Oil Commander www.oillab.co.nz or given as hard copy.

24 elements are analysed in ppm. Also, the flashpoint (°C), viscosity, water, particle count, PQ index (magnetic particles) and microorganisms (HUM bug) readings are given in an understandable form.

In my books, that is an extremely comprehensive and useful test if you are seriously worried about the purity of your diesel. There are ISO standards against which your results can be compared. From these results you should be able to make an intelligent decision on what measures to take to ensure that clean fuel in the tank enables you to reach your destination safely.

PS Advanced Diesel Solutions supplied the author with a L140 De-Bug unit for testing in his 12 metre yacht ‘Wild Bird’.

Post script. The fuel that I can see in the sight glass is clear two years after installing the bug and cleaning things out. Can’t definitively say it was the unit, since we have been using Grotomar biocide. However, last week’s fuel filter changes were indicationg very little contaminants.